Study of the Feasibility of Pyrethrum as a New Crop for North Carolina

go.ncsu.edu/readext?435705

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Jeanine M. Davis, NC Alternative Crops and Organics Program, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University

This study was conducted in 2000-2003. (Reviewed 5/23/2022)

Introduction

Pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium) is a perennial temperate plant with small, white, daisy-like flowers from which natural insecticides, the pyrethrins, are derived. Traditionally, pyrethrum was produced in many African countries where hand-labor was used to plant, harvest, and dry the crop. Political upheaval, drought, and lack of an organized development and marketing structure resulted in unreliable pyrethrum supplies for US manufacturers. In the late 1980s, however, Australia began a pyrethrum development project and is now a major producer of the crop. This has stabilized the industry. Demand for pyrethrum based insecticides is on the rise because of its long safety record, very low toxicity, and rapid breakdown. To quote the late Dr. Scott Chilton in the Botany Dept at NC State University, “Pyrethrum continues to be competitive with synthetic insecticides in the specialized areas where selective toxicity and low environmental hazard are most important. These include use in the control of insects in stored products, in veterinary insect control, as a space spray in the food-processing industry, as a preharvest spray and in other special uses where field laborers must reenter the field within 24 hours. Because of the selective and relatively small-scale use of pyrethrum for over 160 years, there has been relatively little development of insect resistance.” As a result of these characteristics, the use of pyrethrum based products has increased dramatically on organic farms and for home insect control, e.g., mosquito coils. Over the years, there have been several attempts to grow pyrethrum in the US, but poor varieties and excessive labor inputs prevented any serious commercial production from being established. Recently, however, manufacturers of pyrethrum based products have shown new interest in US pyrethrum production. New developments in cultivars and mechanical aids and the suitability of much of the equipment used to raise tobacco may make pyrethrum a feasible crop for some NC producers.

Materials and Methods

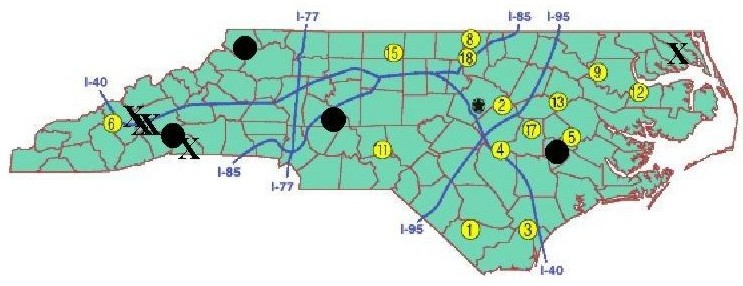

We obtained an experimental variety of pyrethrum from Chile which has many advantages over the commonly used varieties. It has an upright flower habit and blooms all at once, making it possible to mechanically harvest the flowers when fresh. This results in a more potent extract than can be obtained from dried flowers, which are what are harvested in Australia. A prototype machine to harvest these plants was built for use in Chile. The designer of the harvester improved upon his original design and planned to have a prototype built for this project. In 1998 and 1999, we successfully grew a small number of pyrethrum plants in the field and greenhouse at the Mountain Horticultural Crops Research Station in Mills River, NC. In 1999, Dr. B.K. Bhat, an authority on pyrethrum production, conducted a feasibility study on pyrethrum production in NC. His report suggested that pyrethrum could be produced commercially in NC and suggested four areas in the state to attempt to produce it experimentally. He also shared information on methods of production. In the spring of 2000 we set out to evaluate which areas of the state are best suited for pyrethrum production. Three cultigens of pyrethrum (from Chile, Holland, and Germany) were grown at research stations in Mills River, Laurel Springs, Salisbury, and Kinston, NC. The experimental design was a randomized complete block with four replications. At each site, the plants were set on raised beds, 133 feet long, with three staggered rows per bed. At Mills River, Laurel Springs, and Salisbury, the plants were transplanted into bare ground and were irrigated overhead. At Kinston, the beds were fumigated and covered with plastic mulch and drip-irrigated.

Transplants were produced from seed in a greenhouse and field planted in the spring. Survival following transplanting was excellent at all locations. This was unexpected because of extremely hot temperatures during the time of transplanting. We were impressed with the hardy nature of the plants. The biggest problem was weed control. This was most severe at the Laurel Springs site where pigweed quickly carpeted the beds and alley ways. We tested a few herbicides cleared for use on the ornamental chrysanthemum. Devrinol worked well at Mills River but had no effect at Laurel Springs. Data was collected on plant growth, survival, flowering, and overwintering. Flowers were dried, extracted, and analyzed for pyrethrin content.

Transplants were produced from seed in a greenhouse and field planted in the spring. Survival following transplanting was excellent at all locations. This was unexpected because of extremely hot temperatures during the time of transplanting. We were impressed with the hardy nature of the plants. The biggest problem was weed control. This was most severe at the Laurel Springs site where pigweed quickly carpeted the beds and alley ways. We tested a few herbicides cleared for use on the ornamental chrysanthemum. Devrinol worked well at Mills River but had no effect at Laurel Springs. Data was collected on plant growth, survival, flowering, and overwintering. Flowers were dried, extracted, and analyzed for pyrethrin content.

Plants successfully overwintered at all four locations. The flowers were harvested for the first time in 2001. Plants were trimmed back to a height of 6 inches and allowed to overwinter.

In 2002, a large number of plants did not live through the winter in Laurel Springs and Kinston. In Kinston, splits from healthy plants were used to fill in some of the gaps where plants had died. At all locations, the plants were fertilized and irrigated. Flowers were harvested by hand, weighed, dried, and analyzed by a cooperating US pyrethrum product manufacturer. In 2002, Dr. Bhat helped assess the future of pyrethrum for North Carolina based on these research plots. These studies were terminated in 2003.

Results

In 2001, flowers were harvested for the first time. Flower yields needed to be at least 100 flowers per plant to be competitive on the world market. At three of the test locations flowers per plant ranged from 100 to 252. Only the Kinston location had fewer than 100 flowers per plant, but the flowers from that site were much larger than from the other site. The highest yields were obtained in Salisbury. Pyrethrin content of the flowers, however, was too low from any of the plantings for the flowers to be of any commercial value. Total pyrethrin content ranged from 0.49% to 0.95%. Experts in the pyrethrum industry theorized that this was probably due to the young age of the plants and our inexperience in growing, harvesting, and handling pyrethrum flowers. They suggested that we continue our studies for at least another year. At three of the four sites, Rhizoctonia caused a root rot which damaged 1-15% of the plants.

In 2002, there was some winter die-off, particularly in Laurel Springs and Kinston. The greatest loss at all four locations, however, was attributed to Rhizoctonia. Flower yields were highest in Salisbury and well within the commercially acceptable range, but flowers were small. Flower yields were very low at the other three locations. The pyrethrin content of the flowers from all locations was low in 2002, with the best plots ranging from 0.7% to 1%. By 2003, plant stands were reduced by 50% or more in all locations and flower yields were very low.

Dr. Bhat’s final assessment was that the varieties we had were not appropriate for commercial production in North Carolina. Unfortunately, he did not think there was a commercially available variety that would be appropriate for our location. He wrote a report outlining how we could attempt to improve the existing germplasm to increase flower yields, winter survivability, disease resistance and a commercially acceptable level of pyrethrin yield of about 18 lb/acre.

Conclusion

Pyrethrum would take many more years of development before its true potential as a large-scale, industrial crop for North Carolina can be evaluated. In particular, a breeding program would have to be developed.

North Carolina growers are looking for agronomic crops to supplement tobacco, soybeans, and cotton. Many growers had researched pyrethrum and wanted to know if they could grow it and sell the flower extract. Based on the results of these studies, growers should be advised against attempting large-scale production of pyrethrum at this time. As a result of these studies, some growers who were considering growing pyrethrum looked at other crops instead.

In additional to the replicated research studies, there were also five on-farm cooperators in Perquimans, Madison (three cooperators), and Henderson counties. These growers agreed to plant, maintain, and monitor several hundred plants each for comparison with the research station studies. Results were very similar to those at the research stations.

Acknowledgments and the Future of the Project

These field studies were being done in cooperation with a much larger project conducted by Pyrethrum Associates of Linville, NC under the sponsorship and management of Mountain Valley RC&D in Asheville, NC with funding provided by the NC Rural Development Center. Through that project, a business resource manual, an economic impact study, an evaluation and recommendation report from a pyrethrum consultant, and a harvester design were completed.